Literary Theory: Marxist & Alice in Wonderland

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

Exposing the Disposable

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland exposes the plight of the working class of the nineteenth century. Through cleverly crafted characters, including the Queen of Hearts and her playing card workers, Carroll created a literary lesson that brings to light the differences in social class hierarchy, particularly the binary opposition of the upper ruling class and the lower working class. Although the main storyline focuses on Alice and her journey through Wonderland, Carroll’s masterfully poignant and noticeably deficient storyline surrounding the lower working class playing cards, perfectly illustrates the lower working class’ struggles, anxiety, and hardship during a time when the upper ruling class and the bourgeoisie ignored and dismissed them disposable commodities rather than human beings.

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice is portrayed as a member of the bourgeoisie, the Victorian era social class that is a “new class of capitalist merchants” who do not necessarily inherit their fortune, as is true of the upper ruling class, but achieve it through using their “capital to purchase labor through wages, and exploit the labor to accumulate wealth for themselves” (Parker 221). The playing card characters represent the lower working class, who “labor to produce goods and who sell their labor” (221). This class difference is made apparent at numerous points in the story, and while Alice struggles to enter “the loveliest garden you ever saw” or considers the best way to have new boots sent to herself for Christmas, the playing cards struggle to survive in a land where their lives are held in the hands of the brutal, demanding, and impatient Queen, who rules Wonderland (Carroll 15).

Much like any other ideology in the world, the playing card characters are interpellated into the Wonderland ideology as soon as life befalls them. The social and political forces working to perpetuate the Wonderland ideology are so strong, each playing card’s life trajectory and place within the social hierarchy is immediately determined by their suit. The spades are gardeners, the diamonds are courtiers, the clubs are soldiers, and the hearts are the King and Queen’s children. The idea of changing this predetermined purpose in life is incomprehensible to the playing cards, and even if such an idea were to enter into their minds, the social and political forces would prevent such a change from happening. Should one of the playing card characters consider defecting from the Queen’s control, she would undoubtedly have the playing card character beheaded as “the Queen only had one way of settling all difficulties, great or small” (104). Therefore, under false consciousness, the playing cards perpetuate and continue to bring life to the very ideology that will ultimately take their lives.

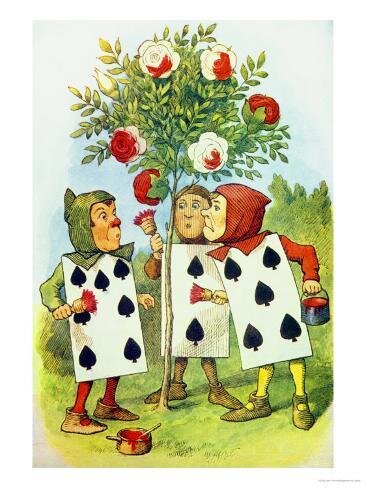

The playing cards, whatever their role in the Queen’s world, are all acutely aware of their position within the social hierarchy and the main force that is keeping them in their place, the Queen of Hearts’ threat of execution. The Queen of Hearts epitomizes a historically typical upper ruling class as she rules Wonderland through the threat of violence. Each playing card character knows that every move they make is potentially their last if the Queen is in any way crossed or inconvenienced by it. In fact, death by beheading by order of the Queen is so commonplace in Wonderland and so ingrained in the playing cards’ way of life that avoiding this tragic fate is the foundation for their every action. This ideology is evident in Alice’s first encounter with the gardener playing cards, who are using red paint to cover the white rose trees that were accidentally planted in the Queen’s garden. The playing cards understand that the Queen would consider this error in tree planting to be a mistake of gargantuan proportion, telling Alice, “if the Queen was to find out, we should all have our heads cut off, you know” (96). Alice sees this cruel treatment and the resulting fear in the gardener playing cards, but when the Queen asks her to simply identify the playing cards, Alice tries to distance herself from the situation by responding to the Queen, “’How should I know? … It’s no business of mine’” (98). Alice’s attempt to disengage from this likely fatal situation at hand is representative of the upper classes turning a blind eye to the oppression and mistreatment of the lower working class.

Further minimizing the importance or validity of the lower working class is the amount of text dedicated to the hardship of the lower working class playing cards. Throughout Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the story of the lower working class is a minor point within the text. Information about the history of the playing card characters, their families, and their ambitions is non-existent. The playing cards as a whole are featured in only one chapter of the book, “The Queen’s Croquet-Ground” and have a very brief but notable mention at the end of “Alice’s Evidence.” Instead, the story is focused on Alice as she stumbles and falls into Wonderland and her journey home. Although many critics could argue that the story singularly details Alice’s adventures, upon the briefest second glance, the lack of inclusion of storyline featuring the lower working class playing cards zeroes in and highlights the dismissal of and irrelevance the upper classes put on the lower working class. This vast void of content to acknowledge and humanize the lower working class is as significant as all of the content devoted to Alice and her personal history, as it represents the great degree to which the upper classes went to deny the personal existence of the lower class population. Indeed, at that moment in “Alice’s Evidence” when Alice mentions the playing cards as a whole, she does so only to dismiss them and whatever imagined power she thought they had over her, stating, “’Who cares for you?’” (145). In this one indignant question, Alice sums up and brings to the forefront the feelings the upper classes have for the lower working class.

The oppression of the lower working class playing cards by the upper classes, and particularly the Queen of Hearts, is felt at every opportunity. The Queen orders beheadings at the drop of a hat and to satisfy even the most remote sense of inconvenience or unhappiness. During the croquet game, “the Queen was in a furious passion, and went stamping about, and shouting “Off with his head!” or “Off with her head!” about once a minute” (102). Carroll called the Queen an “embodiment of ungovernable passion—a blind and aimless Fury” (98). Similar to the upper ruling class being blind to the suffering of the lower working class, the Queen never acknowledges the plight of the lower working class playing cards or the fact that their hardship is a direct result of her brutal actions. The omnipotent oppression the lower working class playing cards felt at the hands of the upper classes mirrors the lack of attention and care the working class of the nineteenth century received from the bourgeoisie and the upper ruling class as they focused only on meeting their own wants and needs.

The Queen’s oppression through brutality and violence is evident in her singular solution to all problems and takes both a physical and emotional toll on the lower working class. The anxiety and fear felt by the playing card characters because of the Queen’s actions is more subtle in the story, but still apparent. For example, when Alice first meets the three gardeners playing card characters, the words “sulky,” “unjust,” “low,” and “anxiously” are used to describe them (95 - 96). All of those words hold negative connotations and represent the feelings, either conscious or subconscious, that the lower working class feels when dealing with the upper ruling class that continuously oppresses them.

Although the playing card characters are in a constant state of oppression and fear for their lives, they allow this oppression to continue because they are so far interpellated into the Wonderland ideology, they wouldn’t even consider attempting a coup of any sort. They never move beyond simply surviving because they are stuck in a state of false consciousness and focused on working for the ruling class and not focused on what is best for them. Knowing the lower working class would never rise up against her, the Queen nonetheless reinforces her status as the ruling power through her constant threat of violence and execution of the lower working class.

Furthering the upper classes’ feelings of dismissal and irrelevance toward the lower working class, the Queen goes through, or consumes, her servants—the lower class playing card characters—as if they are commodities rather than human beings. This commodification shows that the Queen does not view the playing card characters as equal to her on any level. She treats them as if they are disposable material rather than individuals. To the Queen, the playing cards are simply a means to an end, just as Marx would describe the upper class’ exploitation of the working lower class for continued monetary benefit of upper ruling class.

Through the limited content dedicated to the lower working class in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the oppression and hardship of the working class of the nineteenth century is brought to life and highlighted. During a time when the upper classes dehumanized and dismissed the plight of the lower working class, Carroll’s narrow yet descriptive depiction of the lower working class playing cards illustrates the extreme struggles of the lower working class to survive in a social hierarchy that viewed them not as people but as disposable commodities and neither cared whether they lived or died.

Works Cited

Carroll, Lewis, and Mark Burstein. The Annotated Alice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass). Edited by Martin Gardner, 150th ed., The Martin Gardner Literary Partnership, GP, 2015.

Parker, Robert Dale. How to Interpret Literature: Critical Theory for Literary and Cultural Studies. 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2015.